“We have war when at least one of the parties to a conflict wants something more than it wants peace.”

~Jeane J. Kirkpatrick

Last time we had Storyteller’s Playbook, we laid out a basic formula for story structure. Since it’s been two weeks since that last SP, let’s start this one with a review:

A – Open on Action

B – Backstory

C – Conflict

D – Development

E – Ending

Recall that the actual order in which we tackle the elements of our story is not important beyond the fact that we want to make sure that we open with some kind of action or conflict. But then, what is Conflict?

Well, that’s the real question, right? Why are we here? Why should we care?

One of the real tricks in writing is to open your story at the right spot. Just as a lot of beginning writers tend to want to open on Background, so too do they tend to want to start their stories too early. The two tendencies are related. In both cases, the writer wants to make sure that there’s enough context in place ahead of time so that when the real story starts the reader understands what’s going on and why. The thing is, just as opening on Background is generally both boring and unnecessary, so too is opening too early. Readers like the challenge of trying to figure out what’s going on. They do not like to get bogged down in twenty-five pages of basically mindless back story that ultimately has little to do with the main character’s actual problem and its resolution.

So then, what is conflict?

Well, as Ms. Kirkpatrick notes above, Conflict is what happens when somebody wants something more than they want peace. Put another way, conflict is story. Something Happens, and our Hero can no longer sit idly by. He or She must act, decisively, to meet the challenge, deal with the crisis, survive in the midst of danger, or escape an untenable situation. Whatever. Regardless of the situation, we have Conflict starting at precisely the moment when our Hero can no longer continue on as before but must instead Do Something Different. It is that pivotal event that starts our story, and it is there that we as writers should start our story’s telling.

Our Hero wants something. Passionately. From this, we derive our story’s plot.

In my experience, this concept has two primary applications to gaming. The first is that as with any other kind of writing, writing for gaming requires choosing the correct story starting point. In this, newbie DMs are by far and away the most common offenders. Most often, a newbie DM will start his or her campaign in a tavern somewhere long before the campaign’s primary conflict is set to emerge. DMs do this on the grounds that starting this way provides the game’s Players with a chance to do some freeform role-playing up front and/or because it allows the Players to set the game’s general direction. The problem with this is that character in general is formed through conflict. Without an objective or an obstacle to stand in their way, the Players are left to act out their characters’ pre-determined traits and tendencies in a vacuum. There’s no growth going on, and there’s no challenge. Bottom line, nothing important is going on. And the result is often confusion and, if I’m being honest, boredom. In an online setting, Players soon start to disappear until, before you know it, the game has unraveled before it even truly got started.

The other application that gets overlooked by even experienced DMs is the problem of motivation. Why are we here? Why should we care?

In one sense, Opening on Action will resolve at least part of this problem for a DM because action necessarily involves conflict or challenge, and overcoming conflict is a fundamental part of character development. And character development is ultimately what drives the game. I mean, look, the game is fun—even addicting—because of the way that we get to watch our characters grow and mature over time. As Players, there’s a sense of ownership there that makes gaming more fulfilling than any kind of passive ingestion of purely external story material no matter how well conceived or executed. In gaming, we’re actually part of the story. We’re part of the storytelling. We’re actively winning when our characters are overcoming the obstacles that are set in their way. That’s the good part.

And that’s fine. I mean, as a technique, punishing characters is one of the most reliable methods by which a writer can make his audience bond with his protagonists. That’s as true in gaming as it is in comics or drama or film or prose or any other storytelling medium that you want to name. But simply hammering the PCs is not precisely the same thing as providing them with motivation, although it can lead to a certain kind of motivation if it’s done often enough and by the same antagonists. Still, even D&D can be about more than either seeking revenge or saving the world because that’s just what heroes do. The game works better when the PCs want something for a reason that they can easily understand and explain, and at least for my money, if that something is tangible and personal, it’s going to be a lot more effective than if it’s ephemeral or somehow “transcendant.”

One of the things I’m proudest of about my game The Sellswords of Luskan is the fact that against all odds, I think my Players actually care about the fate of Luskan, a city that, not to put too fine a point on it, has done them wrong a time or two. But by living in the city and experiencing its hardships first hand, I think they’ve actually developed real motivation. In storytelling terms, I’ve treated the city itself like a character, punishing it repeatedly in a way that has built my Players’ sympathy—or at least interest—and as a result, they’ve started to care passionately about what happens in their adoptive home and why. It’s not so much that they care for the people of the city or that they want what’s best for them. Instead, for the Sellswords, if anyone’s gonna conquer Luskan, it’ll be them, and death to any with other ideas. But that’s still an emotional investment. It’s still motivation—and a good one. And this, to me, makes the game a lot more than a simple struggle for money, power, or revenge… although all of those things are and will remain part of the story we’re collectively telling.

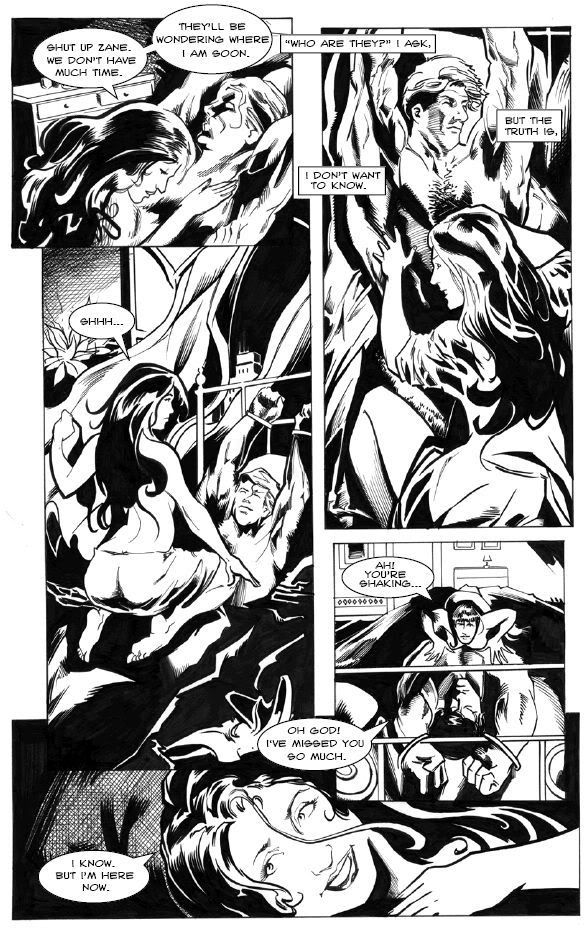

The other thing I want to talk about this week is Development. This is where we ask that favorite question of mine: “What else can go wrong?” Because look, if the ABCDE formula with which we started this week’s column were written mathematically, then Development would be MOST of the equation. In fact, it should be a full 80% of your story. Or, to put it another way, you can pretty much screw everything else up, but if you develop and complicate your conflict competently, then the odds are good that you’re going to be writing entertaining and useful fiction. When I was writing comics, I considered this so important that I would actually go through by page count and make sure that at least 80% of my pages were complications to the existing plotline. Considering that some of my best-known work is actually composed of 6-page webisodes, this was no mean feat.

Fortunately, Development is a lot less tricky an issue in gaming than it is in other types of fiction. Every time you have an encounter, you are essentially putting a new obstacle in the way of your PCs, developing the plot by way of creating ever more difficult hoops through which your Party must jump. That’s at least one of the reasons why D&D is such a combat-oriented game. Combat Encounters are the easiest and most effective forms of plot development available to a Dungeon Master. And since combat is such a large part of heroic fantasy as a genre, why shouldn’t it be?

Still, the need to actively complicate your plot is important, so let’s look at an example using the 80% rule:

1. The Sellswords are shipwrecked on an island.

2. The island is deserted.

3. The ship’s primary cargo was defenseless child-slaves.

4. The waters around the shipwreck are infested with sharks and sahaguin.

5. Once the Sellswords reach land, there is no shelter, and the kids are starving.

6. The ruins of an old pirate settlement were obviously destroyed by a large Black Dragon.

7. The dragon’s lizardfolk minions attack to seize and eat as many of the child-slaves as possible.

8. The dragon’s lair turns out to be very dark and spooky.

9. The dragon itself is a massive beast. Mean and deadly!

10. After killing the dragon, the Sellswords seize the beast’s horde, which turns out to have a small ship in pristine condition. They sail away and live happily ever after.

And there you have it. Sentence 1 Opens on Action, tells as much Background as is necessary, and introduces a Conflict. Sentences 2 through 9 make the Conflict even more perilous. This is the essence of Development. The actual climax of the Story takes place between sentences 9 and 10, and then in 10 we have resolution and a happy ending.

Voila! 80% Development, 20% other stuff.

So there you have it. Creating conflict and motivation is not necessarily easy, but it is necessary if you want to have a campaign story that’s more than just a series of randomly collected encounters with no over-arching theme. Once you have a conflict and a reason for your PCs to pursue their objective, creating complications is easy. The key is to make sure that there are enough complications to make the ultimate reward feel fulfilling. After all, the harder the heroes have to work, the more heroic they will ultimately become. Punish your PCs relentlessly, and ultimately your Players will thank you for the experience.

Oddly, where the graphic novel went wrong—and this despite Butcher’s personal involvement—the TV show got it right. Why? I think it’s because the TV show succeeds in making Harry Dresden look like Harry Dresden. He’s a broke, down-on-his-luck working stiff, and the show goes to pains to show this. For example, my man can’t afford a real magic staff, so he uses an old hockey stick. Brilliant! Different from the books but entirely appropriate given the character they’re trying to create. Plus, Harry is a guy with a sordid past but a heart-of-gold. Again, this is something that the show takes pains to show. That, plus a heapin’ helpin’ of narrative wit and a smattering of plot drawn from the various early novels are more than enough to keep the TV show entertaining.

Oddly, where the graphic novel went wrong—and this despite Butcher’s personal involvement—the TV show got it right. Why? I think it’s because the TV show succeeds in making Harry Dresden look like Harry Dresden. He’s a broke, down-on-his-luck working stiff, and the show goes to pains to show this. For example, my man can’t afford a real magic staff, so he uses an old hockey stick. Brilliant! Different from the books but entirely appropriate given the character they’re trying to create. Plus, Harry is a guy with a sordid past but a heart-of-gold. Again, this is something that the show takes pains to show. That, plus a heapin’ helpin’ of narrative wit and a smattering of plot drawn from the various early novels are more than enough to keep the TV show entertaining.